The Human Nose Took Millions of Years to Evolve, but How We Use it Today Stinks!

The flesh-covered cartilage protruding from the center of your face was the first thing your parents asked you to point at and identify when you were still in diapers.

“Where’s your nose? Where’s your nose? There’s your nose!”

But the toddler test is not the only purpose for this funny-looking appendage shading our upper lip. Deep inside the nasal cavity are Bowman’s glands, better known as olfactory glands—ancient receptors that detect danger, identify genetically acceptable mates, and locate food from a distance.

Sadly, our nose does not get the same dynamic use as our hunter-gatherer past. Safe, climate-controlled habitats and a polluted environment have turned back the clock on our highly evolved olfactics.

Modern humans spend a significant portion of their lives inside man-made structures, protected from nature’s barrage of scented stimuli. Over time, our individual scent library is diminished, limiting the span of our proboscis’ secret powers.

Today, food is a mystery from a nasal point of view. Our nose, poised to get a big whiff of every spoonful of nourishment that passes through our lips, is a useless weapon against processed foods void of identifying characteristics.

We have come to rely on our eyes to do our nose’s job. Rather than walking through the forest, smelling a patch of fresh strawberries in the distance, we drive through town, planning our next feast from whichever billboard drips the most artificial cheese product.

GETTING TO NOSE ONE ANOTHER

Food is not the only thing slipping into our body right under our nose. A study researched by S. Craig Roberts, PhD, and reported by WebMD, suggests a link between oral contraceptives and a woman’s altered ability to detect desirable pheromones.

In the famous t-shirt smelling experiments—where men and women smell t-shirts worn by the opposite sex—women typically choose shirts worn by men who have genetic compositions different from their own, leaning towards males with superior immune systems.

Mixing genes from a broad pool is preferable. Diversity increases the chances of healthy, prosperous offspring. Women on the pill, however, show a decrease in their ability to sniff out favorable pheromones, and instead choose mates who have a similar genetic arrangement.

This is a dangerous combination. If both parties have hereditary defects, there is a good chance they will pass those defects on to their children.

In the article by WebMD, Dr. Roberts said, “If this really happens in the real world, women on the pill would end up choosing a more genetically similar mate than she would otherwise choose and the implications go on from there.”

As the relationship between a genetically similar couple progresses, repulsive pheromones may reveal hidden olfactory warning signs to the subconscious.

Dr. Rachel Herz, adjunct assistant professor of psychiatry and human behavior at Brown University and author of “The Scent of Desire,” says marriage counselors claim odor is a major factor in sexless marriages.

On the Brown University Biomed News blog, Dr. Herz said, “If you can’t stand how someone smells, you cannot become intimate.”

Incompatible pheromones are nature’s way to stop the couple from reproducing and force them to seek out other mates, but a large number of women appear to ignore their biological inner voice.

Jennifer Gauvain, author of, “How Not to Marry the Wrong Guy,” said in a Huffington Post article, “30% of divorced women knew they were marrying the wrong guy on their wedding day.”

Contraceptives are just one factor causing people to commit to the wrong mate. There are a number of other common, everyday activities handicapping our olfactory radar.

Smoking causes decreased potency in our sense of smell, and the smell of nicotine on a potential mate who smokes tricks the nose, mistaking the calming effects of nicotine addiction with pheromone attraction.

Men and women who smoke may have difficulty detecting potential genetic problems with prospects they meet and hookup with prior to a long relationship.

EVERYTHING SMELLS OF SH#%

Imagine if the world around you—the air, people, furniture, clothes, food—smelled burnt or rotten. Or worse, you smell the distinct stench of fecal matter wherever you go—hot fudge sundaes lose all appeal.

This is the horrible disorder known as parosmia. It occurs when the brain fails to identify a scent’s natural odor.

If the odor confusion is a rotting, burning, feces, or chemical smell, yet the patient still encounters pleasant odors occasionally, according to the research paper, “Clinical Presentation of Qualitative Olfactory Dysfunction,” the disorder is more accurately called “euosmia.”

In the book, “Life’s a Smelling Success,” Alan R. Hirsch describes other abnormalities that are equally debilitating, but with a slightly different flavor.

Such as phantosmia, patient who hallucinates [typically unpleasant] smells, hyperosmia, a heightened sense of smell, or the awful, olfactory reference syndrome, a psychological disorder in which the patient believes they themselves have repulsive body odor.

More alarming is the sharp rise in sensory defects, especially extreme conditions like autism spectrum disorder (ASD). TIME Health online reports, “a stunning 57% increase in prevalence since 2002.”

Scientists have not discovered the cause fueling this upward trend, but point to genetic factors, environmental concerns, parental awareness, and advancements in diagnostic techniques.

SOUNDS LIKE TEEN SPIRIT

A landmark study suggests the olfactory system intersects with our sense of hearing, literally overlapping in the brain.

“Historical and psychophysical literature has demonstrated a perceptual interplay between olfactory and auditory stimuli—the neural mechanisms of which are not understood,” says Daniel W. Wesson and Donald A. Wilson, authors of, “Smelling Sounds: Olfactory-Auditory Sensory Convergence in the Olfactory Tubercle”

“Historical and psychophysical literature has demonstrated a perceptual interplay between olfactory and auditory stimuli—the neural mechanisms of which are not understood,” says Daniel W. Wesson and Donald A. Wilson, authors of, “Smelling Sounds: Olfactory-Auditory Sensory Convergence in the Olfactory Tubercle”

In an interesting experiment, they found that anesthetized mice responded to sound odors, “Here we report novel findings revealing that the early olfactory code is subjected to auditory cross-modal influences.”

Wesson and Wilson conclude from their research, “The tubercle presents itself as a source for direct multimodal convergence within an early stage of odor processing, and may serve as a seat for psychophysical interactions between smells and sounds.”

Perhaps this model is why some foods “sound better” than others. With more study, we may learn the positive reaction to smells as clearly as we chart the rankings of number-one hits on the radio.

THE LAST TO GO

In the book, “Making Sense of Sensory Losses as We Age,” Dena Kemmet and Sean Brotherson report hearing loss begins in our forties, vision and touch fade in our mid-fifties, taste declines in our sixties, but we don’t start losing our sense of smell until 75 years of age.

Popular opinion is that taste and smell are related senses, but they are separate and distinct. The combination of the two—what we experience in food and drink—is flavor. The loss of taste reduces flavor significantly, but much of what is generally described as flavor comes from our sense of smell.

Even after a drastic reduction of taste buds in old age, we can envision the feel, texture, temperature, and smell of specific foods to such a degree as to “taste” it. All of these factors contribute to flavor.

PICK A TERM, ANY TERM

Rhinotillexis is the medical term for picking your nose. Rude is the term for picking someone else’s nose.

There is controversy on Wikipedia over the etymology. Experts agree “rhino” comes from the Greek for “nose.” But “tillexis” may either derive from “tillein,” which is “to pull,” or from “Neolatin tillexis,” the “habit of picking.”

Nose picking is more common than you think (or admit). According to a 2001 article in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, “A Preliminary Survey of Rhinotillexomania in an Adolescent Sample,” the average person in the survey picked their nose about four times a day. Those who rhinotillexisiate more than 10-15 minutes daily, may have an obsessive disorder called rhinotillexomania.

Nose picking is more common than you think (or admit). According to a 2001 article in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, “A Preliminary Survey of Rhinotillexomania in an Adolescent Sample,” the average person in the survey picked their nose about four times a day. Those who rhinotillexisiate more than 10-15 minutes daily, may have an obsessive disorder called rhinotillexomania.

Mucophagy, the ultimate taboo, is the act of picking one’s nose and then consuming the mucus orally. Technically, mucophagy is when you eat any mucus, not necessarily mucus from the nose.

Despite the social awkwardness of casual nose picking, it is not entirely condemned. Perhaps society understands that as mucus dries and condenses in the nostrils it prompts an irresistible urge to wrestle with the offending specimen.

Articles on nose picking published in medical journals report the tradition is harmless to the sense of smell and is a natural function of nostril maintenance. Nose bleeds are the most common consequence, though some serious injuries have occurred; most notably, infections from cuts, and breaking through the septum with a determined finger.

On the other hand, so to speak, getting caught picking your nose is embarrassing—a sort of deer in headlights effect, but with a dirty hoof.

Humiliation seems to diminish with age. Older men pick with vigor regardless of gawking bystanders, while younger men utilize the “I’m not really picking my nose” thumb technique. And somehow, the pinky gets away scot-free.

On a social scale, nose picking ranks similar to flatulence, urination, and defecation. We all know these things exist, but it is odd to see them in public.

VIVID IMAGERY OF SMELLS PAST

The sense of smell is like a time machine. To relive a moment from your past, a favorite birthday for instance, you need only smell a cake and you are right back there again. In nature, these smells have a significant influence on our diet, mating, and detecting danger.

If you were unfortunate enough to have a house fire and lose everything—no matter how many times you smell a safe, controlled fire—smoke arouses feelings of dread.

This vivid imagery plays a role in spousal bonds through food association as well. A man, for example, smelling the familiar fragrance of fresh-baked cookies, instantly flashes back to his mother’s baking, and then re-associates a strong feeling of comfort to his wife in present day, strengthening their connection.

According to Kemmet and Brotherson, two researchers mentioned earlier in this article, “Our ‘odor memories’ frequently have strong emotional qualities and are associated with the good or bad experiences in which they Humans can recognize as many as 10,000 different scents, compared with the sense of taste, which is limited to four basic categories: sweet, salty, sour, and bitter. The sense of smell is not only important to taste, but it is also essential for detecting signs of danger, such as smoke, gas leaks and spoiled food.”

Our aromatic memories unlock such intimate emotions because of where olfactory information and memories themselves are stored.

In an article title, “Olfaction and Memory,” The Macalester College Behavioral Neuroscience department said, “The primary olfactory cortex, in which higher-level processing of olfactory information takes place, forms a direct link with the amygdala and the hippocampus.”

The article continued, “Only two synapses separate the olfactory nerve from the amygdala, which is involved in experiencing emotion and also in emotional memory.”

In addition to the close proximity of the olfactory nerve and amygdala, olfactory nerves do not have a myelin coating—known as dielectric insulation—allowing for arcs between smell and memory, explaining the unique relationship of sight and sound.

Scent is the slowest of the five senses, but it endures longer than other sensory memories. The last to know. The last to go. It takes the brain longer to detect olfactory stimuli, yet those memories are stubborn and easily accessible throughout life.

Picture the flash of light when a bulb burns out in your home. Your brain sees the flash instantly and quickly puts together a logical explanation. In contrast, if bread is burning in the toaster, it could take several minutes before your brain recognizes the smell and informs your consciousness to check on breakfast.

People with Korsakoff’s syndrome, a neurological amnesia from a lack of vitamin B1 to the brain, suffer a severe impairment of all other types of memory, except olfactory recollection. According to the Macalester College article, “This suggests that there is in fact a mechanism for odor memory separate from other kinds of memory.”

SENSORY ORDER PLAYS A VITAL ROLE

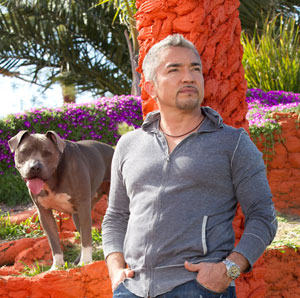

The fifth rule in, “The 7 Habits of Highly Successful Dog Owners,” by Cesar Millan, The Dog Whisperer: “Appreciate Other Perspectives.”

Millan says, “Dogs experience the world through scent, sight, and then sound—in that specific order. It’s vital to remember that fact if we want to communicate correctly with them. The process never changes: nose, eyes, ears.”

When a dog barks because of something seen or heard, Millan suggests holding a treat in front of the dog’s nose to return focus back to their primary sensory input. Dogs are far better at sorting out olfactory information than they are visual or auditory stimuli.

“A guide to canine etiquette would demand that when meeting a dog for the first time you avoid eye contact, exude calm energy, and allow him to simply sniff you,” says Millan. “Thanks to their highly developed olfactory sense—millions of times sharper than ours—sniffing is simply an effective way of gathering information: age, gender, what the other dog had for lunch.”

Humans prefer visual input as their primary source of closeup sensory information, but rely heavily on sound and smell for distant clues. And while sight is a form of instant confirmation, true vetting comes from touch.

When a person hears a noise in the other room, they seek out the sound using their ears to target the source, then investigate visually for the cause and confirm likely suspects with touch—unless, of course, the visual is sufficient—burglar in the living room for instance.

A person who smells or hears potential danger will continue searching for it until there is a visual confirmation of the threat, or from a lack of visual confirmation, the assumption of safety.

BE CAUTIOUS OF HEALTHY ODORS

In addition to keeping us safe from physical danger, olfactory glands are essential for a healthy body. Smelling the air around us lets us know when we are breathing potentially harmful vapors, and scientists claim the mere scent of a green apple aids in weight loss.

But today, those apples and vapors are engineered to play tricks on our better nature. Room deodorizers mask potentially harmful smells and introduce chemicals to the air we breathe. Large corporate farms use pesticides that mimic the food’s natural flavor and keep the bugs away all in one foul move.

By combining our tainted, yet wonderful smelling food supply with an existence protected from the outside elements, we stunt the olfactory features developed over the course of evolution.

The impact of a modern world on human olfaction is sensory deprivation; our sense of smell devolving to mediocrity based on the illusion it is unnecessary.

This is an incredible article.

The only two pieces that really need fleshing out are: how exactly does spending most time indoors diminish our sense of smell?

It doesn’t seem to make sense. When people quit using salt and butter all over their potatoes or vegetables, they report gradually being able to taste the complex flavors of the potato/vegetable on its own. Doesn’t it follow that the presence of more tastes (when using butter and salt) limited their perception of other tastes (the subtler taste of the food itself)? And that being removed from those extraneous tastes for a time enabled them to be sensitive to the subtler tastes of the food on its own?

It seems logical that it would be the same with smells: that being in an indoor environment away from some smells would enable us to be more sensitive to subtler smells.

If by diminishing our smell library, the article means we are losing the ability to IDENTIFY many smells outdoors, then yes I would say that could be true. If you don’t come in contact with a smell and it’s source often, you will not have knowledge of what smells you are sensing. So if that’s what they mean, then it seems pretty correct logically.

The other thing I would love to have read more about is “smell sounds”. It doesn’t really explain in layman’s terms at all what that could mean. What is a smell sound?

Thank You for the compliment and your comments. Indeed, you answered your own question with your second response. Because first-world humans do not rely on their sense of smell as often and to the same degree as we have in our past, we no longer observe and record as many scents.