I recently had the pleasure of reading an unpublished article by well-known skeptic Michael Shermer. As a fan of his books and editorials, seeing an unfinished work—being part of the process—was a welcome experience. Plus, the subject matter was something I have been researching for an article of my own for over a year, which is how our correspondence came about in the first place.

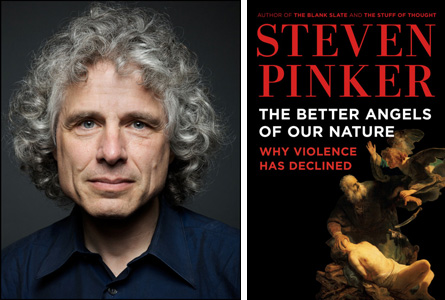

The article you are reading now, however, is not about Shermer’s work, but rather a very small portion of his draft citing another author’s work, Harvard College Professor of Psychology, Steven Pinker, who’s book, “The Better Angels of our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined,” refutes ideas I had come to accept over a long period of time.

I have long been of the opinion that war is a recent invention of the Neolithic, sparse or even nonexistent in the Paleolithic. By today’s definition, war is a struggle between two state societies. 1 Perhaps prehistoric physical violence is better described as unsophisticated raiding?

Semantics aside, it is easy for modern humans to assume war has been around since day one of our species, but from where do we get this assumption? Our written records only go back about 6000 years. Where is the proof that war existed before sedentary agriculture, land ownership, and state societies?

Reluctantly, I mentioned my reservations regarding Pinker’s claims to Shermer. Reluctant because I hadn’t actually read Pinker’s book—my reservations were based solely on the citations in Shermer’s article.

To be clear, I didn’t claim Pinker was wrong, only that his assertions and statistics were controversial based on papers I had read before. After reading his book, I was even more convinced that Pinker’s facts stood in contrast to the published record and accepted theories of prehistoric violence.

I picked up the phone and started calling anthropologists all over the country to see what they thought of the book. With the very first call, my suspicions were validated. A professor of anthropology at a very well respected university said, “[Pinker’s] methods are controversial.” He said Pinker comes at the subject from a “humans are hardcoded” point of view, and uses that perspective to project current behavior on past cultures. 2

Through email, I asked another anthropologist if he would give me his professional opinion on the book. The professor replied, “I must confess that I haven’t read Better Angels.” He said he had only read the reviews, and those “dissuaded me from doing so.” 3

PALEOLITHIC MURDER & THE SCOPE OF PINKER’S CLAIMS

What was so controversial about this book that it had me calling universities and interviewing anthropologists, archaeologists, and psychologists? Instead of quoting from Shermer’s article, I’ll let Pinker speak for himself. Here is a portion of the text from the book that triggered my skepticism:

“What happens, then, when we use the emergence of states as the dividing line and put hunter-gathers, hunter-horticulturalists, and other tribal peoples (from any era) on one side, and settled states (also from any era) on the other?” 4

Introducing his graph, Pinker writes, “The topmost cluster shows the rate of violent death for skeletons dug out of archaeological sites.” 5 And continues, “…in every case, well before the emergence of state societies or the first sustained contact with them. The death rates range from 0 to 60 percent, with an average of 15 percent.” 6

The graph mentioned above, Figure 2-2, is displayed in the Amazon preview for the Kindle edition of Pinker’s book (the first two bar graphs in the book are the two graphs mentioned in this article, both are in the free preview. I suggest taking a look at them).

Nobody denies violence is ancient behavior. But to reach the numbers Pinker suggests takes warfare. The occasional rogue savage couldn’t assassinate 15% of the population. Such a high volume of murder requires significant preparation and the mutual dedication of the group.

The Oxford Dictionary of Archaeology defines a state society as, “Characterized by a strong centralized government, socio-economic class divisions, a market economy and large populations. Settlements are substantial and may be classified as cities with formal planning and monumental architecture.” 7

Today, less than .0001% of the world population lives outside of a state society. But for more than 99% of human history, people lived in non-state societies—groupings of individuals and families into bands, tribes, and chiefdoms. 8

What Pinker claims, is that before the emergence of state societies, when our ancestors were hunter-gatherers foraging the land for food, water, and shelter, they were killing off 15% of the world population by violent invasions, torture, individual homicides, and outright warfare. 9

In Elman R. Service’s, “Origins of the State and Civilization: The Process of Cultural Evolution,” the author estimates the human population of the Earth in 10,000 BCE was about 10,000,000 people. 10 The 10,000 epoch is important here for two reasons. First, it is the end of the last glacial period; 11 a sort of dividing line in human prehistory as the start of the Neolithic Revolution (the transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture and settlement). 12 Second, this is the period of one of the Nubia sites, used by Pinker as his second deadliest example of prehistoric violence. 13

If we are to believe these numbers, then during the biggest chunk of the last ice age, before humans began farming land, we developed such skill in warfare that later, during a time of abundance and vast territories in which to roam, we murdered 1.5 million of our brethren.

Stretch that number over a period of ten years. Did our ancestors have nothing better to do than hunt down and kill an average of 410 people per day? With the exception of fire or a waterway poisoned with the carcass of a dead animal, weapons were mostly one-on-one combat tools, such as spears, rocks, knives, hammers, clubs, and single-shot slings. Killing a million people with these weapons took tremendous effort.

Imagine what life would be like. A constant threat of attack. Within your tribe, you would know nearly two-dozen people killed by fellow tribesman or a neighboring chiefdom. Here is Pinker in his own words:

“The number of deaths per 100,000 people per year is the standard measure of homicide rates, and I will use it as the yardstick of violence throughout the book. To get a feel for what these numbers mean, keep in mind that the safest place in human history, Western Europe at the turn of the 21st century, has a homicide rate in the neighborhood of 1 per 100,000 per year. 14 Even the gentlest society will have the occasional young man who gets carried away in a barroom brawl or an old woman who puts arsenic in her husband’s tea, so that is pretty much as low as homicide rates ever go. Among modern Western countries, the United States lies at the dangerous end of the range. In the worst years of the 1970s and 1980s, it had a homicide rate of around 10 per 100,000, and it’s notoriously violent cities, like Detroit, had a rate of around 45 for 100,000. 15 If you were living in a society with a homicide rate in that range, you would notice the danger in everyday life, and as the rate climbed to 100 per 100,000, the violence would start to affect you personally: assuming you have a hundred relatives, friends, and close acquaintances, then over the course of a decade one of them would probably be killed. If the rate soared to 1,000 per 100,000 (1 percent), you’d lose about one acquaintance a year, and would have a better-than-even lifetime chance of being murdered yourself.” 16

Pinker’s claim—the very subject of his book—is that violence, per capita, has decreased from the beginning of the first “behaviorally modern” humans about 75,000 years ago, 17 18 to today, despite all of the technologically advanced killing machines, bombs, and biological weapons of mass destruction.

He isn’t claiming there was an arc—a period in the beginning where we were tranquil cohabitants—becoming more violent overtime. But rather, we started out vicious, stayed that way for 70,000 years, and then finally learned to live together in a relative state of peace over the last 5000 years.

INVESTIGATING THE EVIDENCE

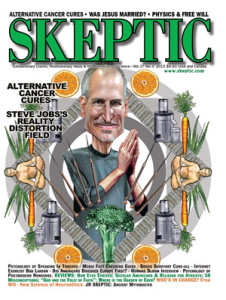

In, “Not Fooled by Randomness,” an eSkeptic book review of Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s, “Antifragile: How to Live in a World We Don’t Understand,” Michael Shermer mentions Pinker’s book with approval: “…take another long-term trend—the decline of violence—thoroughly documented by the Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker in his 2011 book, The Better Angels of Our Nature. This trend has been so slow and steady across so many domains (wars, revolutions, homicide, rape, crime, child abuse, spanking, animal cruelty, racism, lynchings, bigotry, homophobia, and the like) that it took Pinker over 800 pages to document it all…” 19

Shermer is a skeptic. In my opinion, another word for skeptic is journalist—or at least it ought to be. I approach everything, even my own skepticism, from a journalist’s point of view. And I learned very early on, that I have a series of personality traits—maybe flaws—specially suited for journalism.

I am curious, persistent, and willing to be wrong—a “gadfly,” as it were.

The journalist in me reads Pinker’s book with two minds of opposing views—a sort of internal Socratic dialogue. This allows me to explore my own beliefs and question them to an empty core, then rebuild my opinions based on new information.

Instead of calling anthropologists with questions that might agree with my preconceived notions, I asked questions meant to yield an honest response—a free-range conversation rather than a focused interview. I also broadened my base to include other scientific disciplines. Of course, I kept a foot on the side of devil’s advocate too, and fact checked many of the sources in Pinker’s book to gauge the veracity of his facts and figures.

There are tremendous obstacles in the fossil record for Pinker and his claims. But most of those obstacles are holes, not contrary evidence. Pinker, filled in the holes from a well-reasoned, psychological point of view, and ultimately, he convinced me that my original position was wrong.

The traditional view of a peaceful forager suffers from argumentum ex silentio, conclusions drawn from a lack of evidence for or against the theory. Pinker looks at a history filled with clues, not all of which are bones and artifacts, and puts together a thorough examination of violence throughout human prehistory to today.

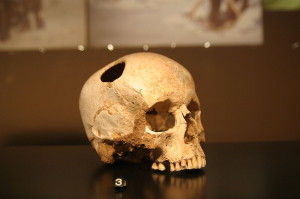

But that doesn’t mean the fossil record stands against Pinker. There are numerous examples of violence in the archeological atlas. The famous, “Ötzi the Iceman,” who lived 5000 years ago, was murdered in the Tyrolean Alps. He had an arrowhead lodged in his should, and Pinker reports, “DNA analysis found traces of blood from two other people on one of his arrowheads, blood from a third on his dagger, and blood from a fourth on his cape.” 20

The “Kennewick Man,” over 9,400 years old, 21 found with a stone projectile embedded in his pelvis. Pinker admits, “Though the bone had partially healed, indicating that he didn’t die from the wound, the forensic evidence is unmistakable: Kennewick Man had been shot.” 22

Ötzi the Iceman and Kennewick Man are two famous examples, but Pinker provides several more lesser-known prehistoric crime scenes in his book. He also includes large-scale archeological finds, such as the Crow Creek Massacre, the Volos’ke, Vasiliv’ka III, Brittany, Calumnata, and Gobero. 23

EXPLORING THE CONTROVERSY

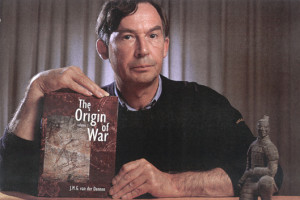

Pinker’s book is controversial not because it is false, but because it is profound. Tradition is a strong force in science, as Pinker notes in the book: “These ‘anthropologists of peace’ (who in fact are rather aggressive academics—the ethologist Johan van der Dennen calls them the Peace and Harmony Mafia) have maintained that humans and other animals are strongly inhibited from killing their own kind, that war is a recent invention, and that fighting among native peoples was ritualistic and harmless until they encountered European colonists.” 24

The opposing view—or rather, the traditionally accepted view—is that why would prehistoric humans wage war on each other before the development of property ownership? How much utility could these primitive nomadic tribes have stored to tempt a rival group? Why risk bodily harm to steal someone else’s food far from your homelands, when there are plenty of things to eat within your own territory? How can small groups kill so many people?

Historian William Eckhardt, whom Pinker wrote is often cited for claiming that violence has increased over the course of human history, said these “bands of gathering hunters” had “little to fight about.” 25 But Eckhardt suffers from presentism—the use of modern ideas to interpret the past. In reality, these early people had a great deal to fight about. Their survival depended on their ability to protect themselves, defensively and offensively.

Pinker wrote, “Many scholars have found the image of harmless foragers to be plausible because they had trouble imagining the means and motives that could drive them to war.” He continues, “But organisms that have evolved by natural selection always have something to fight about (which doesn’t, of course, mean that they will always fight). [Thomas] Hobbes noted that humans in particular have three reasons for quarrel: gain, safety, and credible deterrence. People in nonstate societies fight about all three.” 2627

It makes sense that foraging groups may invade a territory to gain prosperous hunting grounds, a fresh water supply, or even desirable minerals, and they might also “invade for safety,” 28 wherein a small tribe eradicates a larger tribe via ambush to ensure the larger tribe isn’t a threat in the future, but “the most commonly cited motive for warfare,” according to Pinker, “is vengeance.” 29

Here is Pinker in his own words, “Foraging and tribal people avenge theft, adultery, vandalism, poaching, abduction of women, soured deals, alleged sorcery, and previous acts of violence… Tribal people not only feel the smoke welling up in their breasts but know that their enemies feel it too. That is why they sometimes massacre every last member of a village they raid: they anticipate that any survivors would seek revenge for their slain kinsmen.” 30

Pinker uses tribes throughout history, including modern cultures, as examples of prehistoric humans in his book. As argued previously, this method could easily be construed as “projecting,” and himself be the victim of presentism. However, such a fallacy would assume that prehistory describes a specific date in our timeline.

According to Dr. Gary Urton, the Harvard Anthropology Department chair, prehistory is a relative term. He said, “There isn’t a date certain.” Since prehistory is anytime before written records, the term describes a different date for different groups. “Prehistory varies by civilization.” 31

Dr. Urton also said you have to examine the definition of warfare. In prehistory, “[war] was a dispersed affair.” The loss of 15% of the world population from violence among prehistoric humans is “not outrageous.” He said, “War was quite common.” 32

Johan van der Dennen, the ethologist mentioned earlier, wrote in a recent article, “The condition among ‘primitive’ societies is not one of permanent peace nor one of permanent war but can rather be characterized as one of permanent peacelessness, in which the state of war and the state of peace are virtually indistinguishable because these societies are always prepared for war even if they are not actually at war.” 33

The result of peace in prehistory is actually quite deadly. “When peace-loving peoples have occasionally refused to fight,” said van der Dennen, “they have suffered very painful consequences. They usually disappeared—either slaughtered, enslaved, or driven into remote regions.” 34

But how could small groups account for so many deaths? Brute force and a lack of modern social reserve. We picture men fighting men. Male warriors who put up a ferocious fight on the battlefield. But the mortality rate of prehistory is lopsided—the blood of women and children tip the scale—as it is in hunter-gatherer tribes in recorded history.

Pinker tells the story of Helena Valero, abducted in the 1930’s by the Yąnomamö tribe of the Venezuelan rain forest. She witnessed men killing children, “Taking the smallest by the feet, they beat them against trees and rocks… All the women wept.” 35

Pinker quotes another eyewitness, William Buckley, who in the 19th century recalled a firsthand account of one tribe ambushing a camp of rivals, killing nearly everyone present except the women and children. The next morning, the raiders returned, raping the women and killing the children. A few members of the tribe were absent and avoided slaughter. A few weeks later, those survivors went to the raider’s camp, waited for them to leave, and then killed and mutilated their women and children in retaliation. 36

OCCAM’S RAZOR & THE RISE OF GOVERNMENT

Pinker never leaves a single claim to weather on its own, but instead backs up his analysis with extensive examples that support his contentions. For instance, in chapter two, “The Pacification Process,” Pinker compares early humans to our closest living relatives, the common chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) and the bonobos (Pan paniscus, also known as the pygmy chimpanzee). 37

Of the two, the common chimpanzee is more violent than the bonobos, and Pinker argues that Paleolithic humans were probably more like the common chimpanzee and less like the peaceful “hippie chimps” 38 because bonobos have “reduced sex differences.” Species in which the male and female look similar are often more peaceful than those species in which the males and females present extreme differences. 39 There is such an extensive body of evidence to support this idea it is difficult to reason it away, even though the comparison itself is week compared to a more tangible fossil record.

Possibly the best argument for the claim that violence has diminished, is the well-known invention of a significant technology designed with the purpose of limiting violence. Pinker wrote, “The reduction of homicide by government control is so obvious to anthropologists that they seldom document it with numbers.” 40

Government regulation is a popular debate, but there is no doubt that the installation of a state society decreased violent acts in areas and cultures previously void effective rule. 41

FULL DISCLOSURE: PINKER’S CONJECTURE

As a matter of full disclosure, the two charts in Pinker’s book I mentioned earlier, Figure 2-2 on page 49 and Figure 2-3 on page 53, are questionable in my opinion. He cites tribes as nonstate, but a study of those tribes might yield a different label and/or the influence of states is so great to render them a tainted comparison. I don’t think this diminishes Pinker’s conclusions, he cites more than one example and these references are only a portion of his evidence, but it is a vulnerable point in his argument. Also, Pinker routinely cites Lawrence H. Keeley, who’s work I was unable to fact check to my satisfaction. His ideas and interpretations may be valid and widely accepted—I’m not saying there is evidence for suspicion—just that I personally would like to investigate his claims further.

THE LAST QUESTION REVEALS AN ANSWER

For me, the last question was this: If not by war or violent deaths, how did Paleolithic humans die?

The most common cause of death among humans before the Neolithic Revolution is the same as it is today—senescence, or “growing old.” 42 About 150,000 people die per day worldwide, nearly 100,000 of those are of age-related causes. 43 This number varies by location and culture, but barring any pandemics, the percentage reflects the most common cause of death among adult humans throughout history. 44

The average lifespan in the Paleolithic was only 25-40 years old, with men outliving women by a half dozen years on average. 45 The infant mortality rate was very high, 20-30%, and like with modern hunter-gatherers with high infant mortality, if a person makes it through puberty, they have a good chance, about 75%, of surviving until natural death. 4647 48 49

The other 25% of the mature adult population died of food poisoning, premature disease, accidents, and the topic of Pinker’s book, violent deaths.

Falls and drowning were common types of accidental deaths in the Paleolithic, just as they are today. 50 Even if you survived the fall, you might ultimately succumb to a bacterial infection of your wounds (providing you weren’t successfully administered primitive medicine). Malaria developed slowly over 50,000-100,000 years, and then exploded in population about 10,000 years ago with the end of the last glacial period and the beginning of sedentary agriculture. 51

Falls and drowning were common types of accidental deaths in the Paleolithic, just as they are today. 50 Even if you survived the fall, you might ultimately succumb to a bacterial infection of your wounds (providing you weren’t successfully administered primitive medicine). Malaria developed slowly over 50,000-100,000 years, and then exploded in population about 10,000 years ago with the end of the last glacial period and the beginning of sedentary agriculture. 51

Difficult childbirth, diarrhea, respiratory disease, malignant neoplasms and other cancers, digestive disorders, cardiovascular disease, and malnutrition were also factors that accounted for premature deaths in the Paleolithic. When a person developed one of these modalities, however, there was still a good chance they would reach the epoch’s definition of old age.

PINKER’S PROBABILITY IS HIGH

For Pinker’s thesis to be true—an overall decline in violence from prehistory to today—violent deaths need only account for 4% of the Paleolithic mortality rate. An easy number when the fossil record shows the Nubia at over 40%. And to add to the sheer amount of data in Pinker’s favor, a portion of violent deaths were caused by animals. Humans were, after all, a food source for tigers, bears, and even other humans.

Pinker quotes Sir Henry Maine, the 19th century British legal historian, known for pioneering the study of primitive law and anthropological jurisprudence, 52 “War appears to be as old as mankind, but peace is a modern invention.”

Two months ago, I said 15% of the prehistoric population dying a violent death was unlikely. Today, I agree it is a comfortable average. In some cultures, the percentage was much higher. By questioning what I believed—fact checking sources and talking to experts in the field—a new opinion developed; one backed by more evidence and stronger conviction.

Pinker’s claim that [human] violence has declined over the last 75,000 years may be controversial, but it isn’t ethereal. His book, The Better Angels of our Nature, is well written, well reasoned, and relevant in today’s national conversation. Shermer called Pinker’s book, “One of the most important works of social science ever produced.” 53 I agree on one caveat, that we accept its message: state societies have a governing role to play in reducing violence for future generations. ![]()

Funny how you didn’t cite or interview R. Brian Ferguson (Rutgers) who presents an equally strong case that there was no warfare until the early Holocene.

I’m curious (naturally), how you know if I did or did not interview Ferguson? A year ago, I would have agreed with Ferguson’s argument, but I can’t today. His paper focuses on war. The word itself is an invention of the Holocene, violence in general, however, is evident in the Paleolithic.

Alright, I don’t “know” you didn’t read Ferguson, it just seemed so from your article. He’s probably been the most prolific of the opposing viewpoint, so it would seem reasonable that if you had read widely, you would have stumbled across his work. The absence of his name from your article I inferred as unawareness. I’m glad to be corrected on this.

Incidentally, Ferguson has more than a “paper” about war, he has a whole corpus.

Joe, I would have responded to all of your points in my previous reply, but for some reason they only just now appeared on my screen. Here you go…

1) I had made the same argument, but it’s wrong for two reasons: presentism in both definition and culture, and argumentum ad ignorantiam. If two groups of early paleolithic humans are at “war,” and 15% of their population die, that may only be two people (and not all at once). Later, as the population grew, so did the death counts. Only then were there non-state mass graves, and Pinker cites them in his book.

2) You don’t need to know the population to draw a conclusion. Though population estimates can be, and often are, used to support these conclusions.

3) Originally, this was one of my strongest arguments against Pinker. After reading current research and talking with anthropologists, I discovered there is far more evidence than I thought (argumentum ad ignorantiam). Devote yourself to the subject, critically analyzing the data, and you will find enough evidence to keep you busy the rest of your life.

4) Pinker is simply describing the culture so that the reader understands the long history of anthropologists ignoring evidence contrary to their own conclusions regarding prehistoric violence, and how some of them would lash out against opposing viewpoints.

5) You will have to ask Pinker about his title (or read his book if you haven’t already). You can also include animal-related violent deaths when factoring today’s mortality rates to make a fair comparison. Regardless, Pinker is still correct in his thesis.

6) You said, “almost solely.” That is the answer to your question.

7) Your argument is answered in my article.

8) Prehistoric rape, while a violent act, probably didn’t account for many deaths at all (more presentism here). Ancient childbirth is deadlier than ancient rape. Violent sex was just sex among primitive people. The gentle art of lovemaking suffered from a lack of candles and soft music in the Paleolithic.

9) Pinker addresses enforcement in his book. But regardless, your argument assumes every arrest is an act of violence. That is false.

10) Already addressed.

I appreciate your reading my article and taking the time to respond. Cheers!

Mr Gadfly, Can you define what “an act of violence” is? Why would State Violence not be considered violent? What is the basis for this bias?

State violence is a factor, but you cannot discuss states before states existed. Here is Pinker’s definition of violence: http://stevenpinker.com/pages/frequently-asked-questions-about-better-angels-our-nature-why-violence-has-declined

His entire thesis is based on the notion of a decline in violence. Hence current times could not be more valid. Thus state violence has not be made a factor in his analysis. The other thing that bothers me is how he has just sidelined the works of Ferguson, whose work makes it clear that warring and violence was rare to none existent prior to 7 000 years ago (I will check on that timeline again to be certain. There is much that Pinker ignores in making his thesis.

It sounds like you haven’t read my article, or Pinker’s book. And if you think violence was nonexistent 7000 years ago, you have even more reading to do.

I have read your article and have read of the main arguments in the book and sadly it seems that you and he are cherry picking the evidence to make your theses. Sorry but there is a great deal of evidence that has been missed out in making your cases for Neo Con imperialism and its so called civilising effect on the world.

The exact opposite is true. For years, people cherrypicked data to erroneously describe human history—sometimes they got it wrong on accident, other times there was an agenda. Today, consensus is on Pinker’s side. Call the leading anthropologists and ask them their thoughts. That’s what I did for this article.

But Ferguson et al make it clear that they do accept that the evidence supports warring and violence in Humans up until 7000 years ago. He (Ferguson) then points out that many experts then simply extrapolate and make assumptions as he states that the evidence for man upon man violence is just not present. Hence these opinions are not evidence based so my speaking to lots of “experts with opinions” will not help me, as Mr Pinker’s book does not really help Humanity with his opinion.

I presume the articles that offered a view might help with why I feel so disappointed with Mr Pinker’s work.

One has to ignore a great deal of evidence to come to the conclusions you have. Humans did not suddenly become violent, nor is war the only form of violence. Also, you seem to be stuck on this “7000 years ago” number, but not all civilizations were civilized at the same time. I hope you continue your reading, and hopefully incorporate more materials that are not conspiracy-theory focussed. Cheers!

Very amusing, I think you will find that you are the one in the blind alley. I explained where the 7000 figure came from. You are revealing the weakness of your own mind here. You say that you spoke to many anthropologists but the information has not been properly presented to show what you asked and in what context and the response so that any of us could see who was leading who or if the questions and responses really might have another interpretation. And if you think the rich and powerful do not conspire (conspire = to breathe together) then you really are living in a fantasy world and none of what you say has relevance. Having sent a few more views from academics that reveal the holes in the argument of Pinker and you ignore them, it does cause me to ask, just what is your purpose Mr? Cheers. If I ever find a Mr Gadfly article in paper format ever .it will take pride of place, next to the lavatory, where a useful function will be found for it.

On the contrary, my sources are cited above, and Pinker’s sources are cited in his book. You’re focussing on a very narrow, outdated and mistaken view. The articles you posted were really nothing more than rants by people riding on Pinker’s fame.

Then something is seriously missing, your article is not academic and saying that you have spoken to someone and not saying what the actual question was and in what context and the actual responses tells us nothing but what your opinion is. You do not know my view, I have not stated it. Again an error that reveals much to us. The articles that I presented were not mere rants they offered a rational counter to Pinker’s book. Saying they were rants and that your sources were all right is very “school ground” Mr Gadsby.

It’s getting even more difficult to believe you read the article in full. Your most recent comment reveals you didn’t even read the title. Again, I cited my sources, which you admit are unfamiliar to you firsthand. Research the subject, and come back when you’re ready to discuss your views. Speaking of “school ground,” thanks for printing my essay!

Oh so now you admit these are just views. Nice. Just that some of your responses to readers on here led me to think you were on the position of “right”. Ok thanks.

Of course, an essay I wrote on my blog is my view. You shouldn’t have to be told that, especially since it’s in the title. My views were updated based on the new evidence presented to me before I wrote the essay, and published in the academic world over the past two decades—this too, is in the article. If you have evidence to the contrary, post the studies and I’ll take a look.

The thing is that I doubt that whatever I sent would make any difference. There is no consensus on this matter as the views of many academics that I have read seem to show. You are “at this time” in what appears to be the latest popular position. Yet the blank slate v hardwired and the flexible approach continue to exist with the current evidence. The current evidence has not suddenly emerged at all from nowhere, but certainly your views have. I seem to not be getting through so I will bid you adieu.

I agree that Pinker has written a view, I agree that some of it was based on evidence. However, his thesis is not scientific and research based directly at all and has been exposed as such many times by those who can work this stuff out. Hence he and you are entitled to your opinions, but that is all they are. Nothing more nothing less. Thanks for that. Now just let go and expand your own mind beyond that of the borrowed stuff of borrowed minds. Learn to really work out what is and what is not in the world. Cheers.

Isn’t State monopoly of violence recorded as violent in Pinker world? I would like Mr Pinker learn about the history of violence in Colombia, and the very concept of warlords… You telling me if it wasn’t for the warlords people are more violent to each other? Really? Someone is investing in such arguments…

No, warlords are a violent element. Without them the violence would be less in an ideal plane. Likewise, the warlord’s violence might be greater if they existed within a system without a constitutional government.